Design Patterns in the Wild: Builder

Builder

Intent; “Use the builder pattern to encapsulate the construction of a product and allow it to be constructed in steps.” (HFDP)

A successful application of a builder pattern always starts with realizing that we are trying to create an object that is highly configurable. We could use a simple constructor to pass all the arguments, but we might end up with a huge amount of parameters that need to be fed into it. So, the standard solution to this problem is defining a separate class that will provide methods for configuring the object. We will gain not only the clarity of the construction of our target object. The pattern also gives us a possibility to vary the order of application of different options and even a chance to separate the application of different options into non-consecutive steps.

So we have established our basic framework - we have one target class (or even better an interface) and one builder class (or also an interface). Clients will always only interact with the builder. After initializing it, they will set all the desired options on it, and at the end, they will call some method that will return an instance of the target class. That way we are able to hide all the implementation details about the target class from the client. As a result, we are even able to switch the implementations when needed.

x509 Certificates

The use case I have chosen for the builder pattern is a generation of public key infrastructure objects by a Python x509 library. I will make the case only for the x509 certificates, but a similar logic applies to other classes the library implements (like certificate signing requests or certificate revocation lists). PKI certificates are certificates that are the backbone of (not only) internet security and provide a mechanism for participants to verify the authenticity of peers. When your internet browser wants to securely talk to some domain, it will start by asking the webserver behind to domain to send its public certificate. After obtaining it, the browser will try to validate that the sent certificate was signed by a Certificate Authority the browser trusts (these CA certificates are bundled together with a browser).

Each x509 certificate needs to contain a public key itself, a subject name (i.e. some identification of the certificate holder), serial number, start and end dates of its validity, details about the issuer of the certificate, algorithm of the certificate’s signature, and some more options. There are also some fields that are non-configurable but are added to the certificate, like the signature of the certificate that is created by the issuer and serves as a stamp the will give clients the guarantee that they can trust the certificate (if they already trust the issuer). A large majority of language-specific crypto libraries will bind to some battle-tested cryptographic C/C++ implementations, like OpenSSL or BoringSSL, to sign certificates (there are some exceptions, like Golang, that contains its own full-fledge cryptographic library).

Python x509 library

How could we approach modeling this functionality of issuing valid PKI certificates as hypothetical authors of the x509 library? We might start with thinking that we could create a single class Certificate that will contain methods to get and set values on individual attributes. However, as we said, some attributes (like the certificate’s signature) of the certificates are generated and are therefore read-only. Differentiating these read-only and write-only attributes could create significant confusion amount the users of our library. These read-only attributes are only possible to obtain after signing the certificate, therefore the class would contain attributes that would make sense only after some specific method of the certificate is called. This doesn’t sound very pretty.

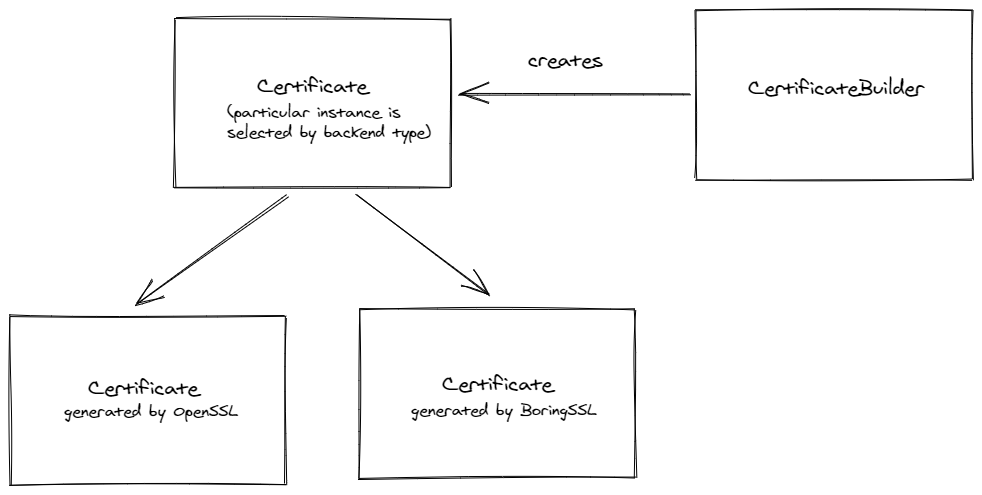

What about using a builder pattern here - we have a lot of configuration options and we could use the split between building a certificate and the certificate object itself to demarcate precisely what are read-only and write-only attributes. Our design might therefore consist of Certificate and CertificateBuilder components.

Certificate class will be read-only and will be the result of the certificate signing. It can store all its attributes directly or it can lazily fetch its attributes from the underlying cryptographic implementation by passing the generated certificate bytes for the purposes of memory and performance efficiency. To operate the Certificate class we will need another class that we can call CertificateBuilder and that will be used to set up options for the certificate. When the clients will need to fetch the final certificate, they will call a method of CertificateBuilder that will return the signed certificate. Due to the fact that we might want to support multiple signing backends (it might be because of performance reasons, or due to some platform-specific requirements), we might create a Certificate interface (or ABC in Python’s lingo) that will be implemented by different backends. So a UML diagram from an aspiring young artist might look like this:

As you might have guessed, I have described before more or less an implementation that the authors of the Python library have chosen. Let’s see how some of the methods for CertificateBuilder are defined:

class CertificateBuilder(object):

def __init__(

self,

issuer_name=None,

subject_name=None,

public_key=None,

serial_number=None,

not_valid_before=None,

not_valid_after=None,

extensions=[],

):

self._version = Version.v3

self._issuer_name = issuer_name

self._subject_name = subject_name

self._public_key = public_key

self._serial_number = serial_number

self._not_valid_before = not_valid_before

self._not_valid_after = not_valid_after

self._extensions = extensions

def issuer_name(self, name):

"""

Sets the CA's distinguished name.

"""

if not isinstance(name, Name):

raise TypeError("Expecting x509.Name object.")

if self._issuer_name is not None:

raise ValueError("The issuer name may only be set once.")

return CertificateBuilder(

name,

self._subject_name,

self._public_key,

self._serial_number,

self._not_valid_before,

self._not_valid_after,

self._extensions,

)

"""

Here are some other methods that prepare attributes of the final Certificate.

I have omitted them for the sake of brevity, as they implement a very similar

logic to the issuer_name method.

"""

def sign(self, private_key, algorithm, backend=None):

"""

Signs the certificate using the CA's private key.

"""

backend = _get_backend(backend)

if self._subject_name is None:

raise ValueError("A certificate must have a subject name")

if self._issuer_name is None:

raise ValueError("A certificate must have an issuer name")

if self._serial_number is None:

raise ValueError("A certificate must have a serial number")

if self._not_valid_before is None:

raise ValueError("A certificate must have a not valid before time")

if self._not_valid_after is None:

raise ValueError("A certificate must have a not valid after time")

if self._public_key is None:

raise ValueError("A certificate must have a public key")

return backend.create_x509_certificate(self, private_key, algorithm)

I have removed all methods that prepare certificate’s attributes except issuer_name, because they resemble each other in their internal logic. These functions check whether the provided arguments are valid, and if they are, a new CertificateBuilder instance is returned. I am not completely sure why the authors decided to return a completely new instance in contrast to returning just self, but I suppose that it might be connected with their desire to provide users the possibility to easily create multiple certificates that have a lot of attributes in common.

At the end of the code excerpt, we can see the sign method that will firstly check the validity of certificate attributes and then return the signed Certificate by calling the backend’s create_x509_certificate method. Backend is just some implementation of X509Backend interface and a currently used backend is just a wrapper around an OpenSSL library. create_x509_certificate method returns an instance of x509.Certificate interface, which is also backend-specific. Authors of Python’s x509 have decided to fetch certificate fields lazily, so for most of the attributes of the certificate implementation, you can see the calls to the underlying library wrapper. My guess why the authors decided not to load all the parameters of the certificate is to optimize memory and performance efficiency as the majority of users will need only to access a restricted set of attributes.

Possible user interaction with the library is shown below. I reproduce here only a part of the code where I generate a server certificate, but the whole snippet containing also a generation of a CA and subsequent start of an HTTP server can be found here.

# Generate the server's RSA public-private key pair

server_rsa = rsa.generate_private_key(

public_exponent=65537,

key_size=2048,

)

# Generate the server's certificate

server_cert_name = x509.Name(

[x509.NameAttribute(NameOID.COUNTRY_NAME, "CZ"),

x509.NameAttribute(NameOID.STATE_OR_PROVINCE_NAME, "Prague"),

x509.NameAttribute(NameOID.LOCALITY_NAME, "Prague"),

x509.NameAttribute(NameOID.ORGANIZATION_NAME, "DesignPatternsInTheWild"),

x509.NameAttribute(NameOID.COMMON_NAME, "DesignPatternsInTheWildServer")]

)

server_certificate_duration = 30 * datetime.timedelta(1, 0, 0)

server_certificate = (

x509.CertificateBuilder()

.subject_name(x509.Name(server_cert_name))

.issuer_name(issuer_certificate.subject)

.not_valid_before(datetime.datetime.today() - datetime.timedelta(1, 0, 0))

.not_valid_after(datetime.datetime.today() + server_certificate_duration)

.public_key(server_rsa.public_key())

.serial_number(x509.random_serial_number())

.add_extension(

x509.BasicConstraints(

ca=False,

path_length=None

),

critical=True,

)

.add_extension(

x509.ExtendedKeyUsage([x509.ExtendedKeyUsageOID.SERVER_AUTH]),

critical=False,

)

.add_extension(

x509.SubjectAlternativeName([x509.DNSName(u'localhost')]),

critical=True,

)

.add_extension(

x509.KeyUsage(

digital_signature=True,

content_commitment=False,

key_encipherment=False,

data_encipherment=True,

key_agreement=True,

key_cert_sign=False,

crl_sign=False,

encipher_only=False,

decipher_only=False,

),

critical=False,

)

.sign(private_key=issuer_rsa, algorithm=hashes.SHA256())

)

The snippet starts with generating a private key instance. Then we initialize a new CertificateBuilder, on which we set attributes of the desired certificate. In the end, we just call a sign method, which will return the final certificate. We can see how we are able to chain the methods for specifying the certificate’s attributes.

To summarize, using builder pattern for generating and signing certificates allowed us to specify individual certificate attributes in a very straightforward manner, while also keeping a clear distinction between settable and readable attributes of the certificate.

Source: Python Cryptography Library